Dialogue

2020, performance with limestone. Video stills and excerpt from HD video with sound, 6 hours 55 minutes, edition of 3 + 2 AP. Performers: Emma Fielden and Tarik Ahlip. Videographer: Dara Gill. Commissioned by Parramatta Artists’ Studios Rydalmere for NEXT.

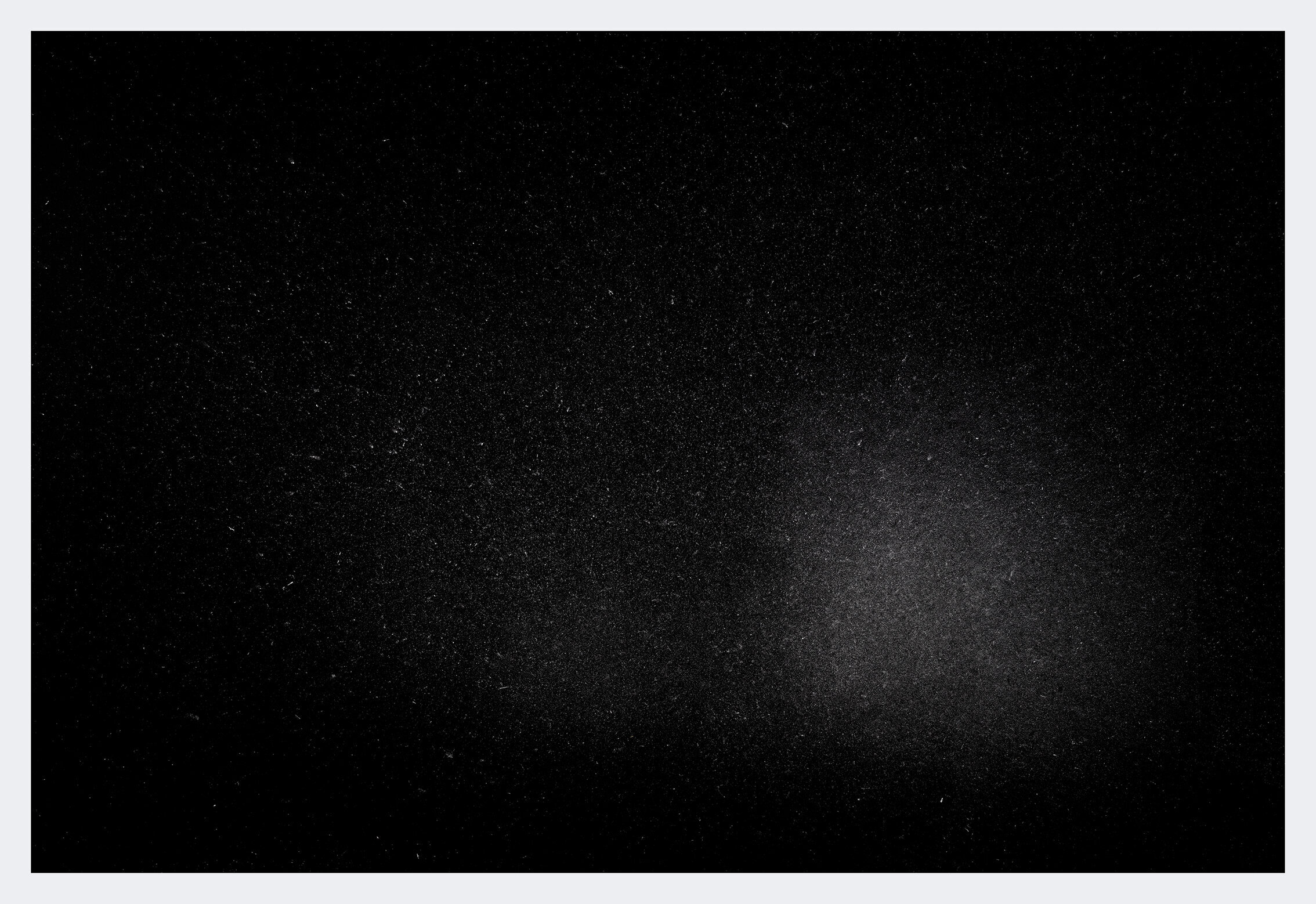

Emma Fielden’s ‘Dialogue’ is a durational performance in which two people attempt to transform a 1-tonne limestone boulder into rubble. As they do so, shards of limestone are flung at the black walls behind them, making two wall drawings with cosmic implications. These wall drawings carry a subtitle, ‘Dialogue (a thousand butterfly skeletons sleep within my walls)’, borrowed from Federico Garcia Lorca’s poem ‘Hours of Stars’.

Dialogue (a thousand butterfly skeletons sleep within my walls)

2020, photographs of wall drawings from the performance space created as a result of the performance (limestone on black walls), pigment print on cotton rag paper, each 117 x 170cm, edition of 5 + 2AP. Photographer: Sarah Kukathas.

‘Dialogue’ video and limestone remnants of the performance installed at Dominik Mersch Gallery.

‘Dialogue (a thousand butterfly skeletons sleep within my walls)’ installed at Dominik Mersch Gallery.

EMMA FIELDEN: DIALOGUE

By Julie Ewington

Performance Video:

Performers – Emma Fielden, Tarik Ahlip.

Videographer – Dara Gill

Duration – 6 hours 55 minutes

Commissioned by Parramatta Artists’ Studios Rydalmere

Instructions:

A limestone boulder.

Two performers simultaneously enter the set, one from stage right, one from stage left, each holding a stonemason’s hammer.

They take their place on the floor facing each other at either side of the boulder.

Together, they begin to hammer the boulder.

Their blows fall in and out of synchronicity, rhythmic, almost musical.

They continue until the boulder is transformed to rubble.

Throughout the duration of the performance, the performers may leave and re-enter the set at any time.

. . .

Emma Fielden’s brief instructions set the scene for an unfolding poetry of cosmic implications. This seems unlikely at first reading. Yet from the start of the video, when you see the black studio space and the performers’ black clothes, and they start hammering away at the white limestone boulder, you begin to register the multiple dualities invoked here. White and black, and by implication day and night, positive and negative, particularity and immensity, compressed and expanded time, the necessary complicity between creation and destruction. A woman and a man. Many forms of dialogue. But no speaking. Only the singing clashing of stonemason’s mash hammers, occasionally a chittering as a small shard skitters across the floor.

The work is backbreaking. It is shocking to watch, this voluntary engagement with the hardest of all labours. The space is marked by clouding stone particles and flying splinters; some solid chunks litter the floor among the bright debris of smaller chips. And you see the white dust settling on Emma’s bent back, in her hair. The two work steadily, relentlessly, with regular breaks for water, new band-aids for blistered hands, occasional sustenance; the movements gradually become more laboured, the two bodies move slower; by the six hour mark they are both evidently sore -— stretching and twisting arms and wrists, hunching shoulders. Fielden’s partner in Dialogue is Tarik Ahlip — sculptor, architect, poet, resident at Parramatta Artists’ Studios between 2012-2016 — whose practice with stone nicely complicates his complicity here.

The two hammers strike percussion from the stone. Their different rhythms are discernible, mostly random, sometimes in counterpoint, only occasionally in unison. That the two performers are physically distinct also matters, even as their task is identical. The sonorous sound patterns notate the particular physicality of two performers: each addresses different sides of the boulder, from different heights and angles, whether standing or kneeling; Tarik tends to land huge blows right after his regular water breaks, Emma pounds away doggedly. The two walk around the limestone, sizing it up, considering the next moves. Occasionally one stands back, the other steps forward to work. Afterwards Fielden describes Dialogue, with understatement, as ‘intensely laborious’. And clearly this work is a meditation of sort: ‘…around the six hour mark I started to feel my energy slip the most. But then when we fell into a new way of working together for the last hour and a half or so, my energy lifted and the pain in my hands and muscles became far more bearable, it even seemed to disappear…some sort of heightened state certainly kicked in.’ ¹

Who would have thought that Australian limestone, the sedimented residue of the vanished inland seas and innumerable marine creatures, could be so resistant? Dialogue is an exercise in persistence, in discipline: the arduous repetition of small actions here reverses the long environmental processes that made the stone, the geological time that is compressed into its substance. By enduring for almost seven hours, Emma and Tarik’s actions respect the longevity of the limestone, which is not, even at the end of the prescribed period, transformed into the pre-ordained rubble of the artist’s expectations. The boulder has resisted their onslaught, remains impressively large: on this occasion, human intention is thwarted by this obdurate chunk of nature.

Conversely, in its encounter between human labour and a natural material Dialogue explores — analogically, through its modus operandi — the infinite expanse of the universe. Since 2018 Emma Fielden has made several videos with paired performers and actions that have emerged from her long investigations of structuring dualities, and which suggest possible approximations of the cosmos. We are two molecules floating together in space and our distance is infinite, then the sound of birds (2018) and Andromeda and the Milky Way (2019) are both videos of two performers working in unison, in the first case with small stones, in the second drawing with charcoal; A Diminishing Force (2019), a two-channel HD video, shows the artist’s hands using a metal hammer to pulverise, apparently simultaneously, small blocks of white marble and black ferrite magnet, materials with markedly different properties. With Fielden it is always a matter of precision: the materials are few, the chosen actions simple and repeated, but the implications enormous.

In deciding to work with stone, Fielden considered the many narratives of classical mythology — Pygmalion creating the living Galatea from inanimate marble, Medusa turning men into stone, Sisyphus and his eternally rolling rock — that speak of creation and destruction. This is significant because European sculptors, at least since the classical Greeks, gloried in carving marble, which is a close geological relation of limestone. Fielden’s one tonne boulder was sourced in Brown’s Creek in central-western New South Wales, most of it subsequently transformed, unlovely, into cement. With Dialogue, however, this particular location, this one stone, enters into conversations about metaphoric (and metamorphic) processes in European art that run from the philosopher Plato and his dialogical method of knowledge through to Samuel Beckett’s late modernist performance works Quad I and II (1981/1984).² What brings these materials and histories into play yet again, in a Rydalmere studio in western Sydney, is one more search for an encounter with natural materials that will invoke the widest parameters of the cosmos.

Emma Fielden has been chipping away at this question, then, for some time — human agency set in the vastness of creation. It is poignant to consider the effort required simply to register human presence, to find meaning in the vast darkness and light of the universe. But this is what we do, and this is what we see here, even if we understand what we are doing only imperfectly, or after the event. With Dialogue, one effect of Emma and Tarik’s prolonged labour was the appearance of myriad constellations of white marks on the black surrounding walls, made by flying limestone chips and dust. These are the most minute particles of what once cohered in that one tonne boulder: we ‘see the Universe in a grain of sand’, as William Blake said, ‘Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour’. ³

NOTES

1. Email from the artist, 10 September 2020.

2. Samuel Beckett’s Quad I and II (1981/1984) were seen by the artist in the exhibition Centre Pompidou Video Art: 1965-2005 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney in 2007.

3. See William Blake, Auguries of Innocence (c.1803), in (ed. Geoffrey Keynes) The Complete Writings of William Blake, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp.431-4.